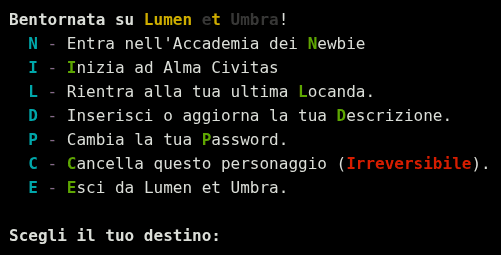

After my interview with Joseph about the Worldmap Project, I asked him who I should talk to next. He pointed me in the direction of one Niymiae, admin of Lumen et Umbra, an Italian game that’s been running since 1994.

Joseph described Niymiae’s work on LeU’s map as “absolutely stunning,” citing its deep lighting system and real-time updates as a direct inspiration for his own design.

Intrigued, I reached out, and Niymiae agreed to share his story.

Read on to learn how a Diablo rivalry led Niymiae to multi-user dungeons (MUDs), what sets Lumen et Umbra apart, and why he spent nearly 6 years on a major release for the game. 😲

Table of Contents

- Meet Simone: keeper of Lumen et Umbra

- Wearing all the hats

- Lumen et Umbra: breaking free of the Diku mold

- Challenges in game progression

- Building for accessibility

- Lessons learned while rebuilding LeU

- Advice for aspiring developers

- Looking ahead: what's next for LeU?

- Acknowledgements

- Frequently Asked Questions

Meet Simone: keeper of Lumen et Umbra

Simone, better known online as Niymiae, has lived most of his 41 summers near the walls of Rome.

When he isn’t working on Lumen et Umbra or being a responsible adult, he tries to maximize his time doing other things he enjoys, like studying games, thinking about game design, looking for game inspiration, and… yeah, he’s pretty into what makes games tick, it turns out!

(Welcome to the club. 👀😂)

His career has taken him through several branches of IT, but he spent the past decade working as a level and mission designer for simulators.

“I hope I can keep my work on Lumen et Umbra on the good side of that terrible, terrible fence,” he told me, referring to the fine line between passion and work.

Discovering MUDs through rivalry

Simone’s introduction to text-based games came in 1996, when he was 12 years old and heavily into the original Diablo. As the community started to decline, his biggest rival suggested they move to a new arena: MUDs.

The two started on an Italian game called Clessidra – still online today! – before moving on to Lumen et Umbra.

At first, Simone stuck around for the rivalry and competition.

“My first foray into MUDs wasn’t particularly successful, and I felt compelled to rise up to the challenge,” he recalled. Rivalry eventually gave way to connections: he met friends, attended in-person meetups, and later migrated with them to World of Warcraft.

Even after moving on from MUDs as a player, Simone kept looking back. In the early 2000s, he joined the staff of a new game where he wrote setting lore, built zones, and organized live events.

“It was a great time, I loved everything about it,” he said.

Unfortunately, the project collapsed after some drama. His password was stolen, his staff character was misused, and the fallout ended the game.

That clipped experience lingered with him, though.

“It always felt like something unfinished and left hanging, and I kept thinking about it regularly,” he said. Players from that community reached out to him for years afterward, asking if he would ever start something new.

“I wanted to, but I had no idea where to find a working codebase, and no clue in how to set things up.”

Finding a home in Lumen et Umbra

Over the years, Simone made several attempts to start a MUD of his own. He even applied to join another project’s staff, but health issues forced him to step back before he could follow through. Later, a friend pointed him toward Lumen et Umbra, which was looking for help.

He applied without much expectation and was surprised at how quickly he was accepted, though his role was minor at first.

“My wife still likes to remind me that I told her this endeavor would probably last a month or two,” he said. “At this point, it’s been almost ten years.”

Wearing all the hats

Today, Lumen et Umbra is largely a one-man operation.

“Currently the staff is, for the most part, me,” said Simone.

A few players help with the helpfiles and Mudlet package, but most of the work – from code maintenance to content design – falls on his shoulders.

It wasn’t always this that way. Years ago, a new system was implemented that led to some unfortunate fallout among the game’s staff.

The system let players build their own realms, set up armies, and raid each other for resources. It sounded ambitious on paper. In practice, the feature was incomplete and problematic, resulting in numerous complaints.

Simone tried to mediate, but his influence was limited. Ultimately, the community fractured.

“My best wasn’t enough,” he said, still regretting how things played out.

When the dust settled, he was left holding the reins of the game. Rebuilding trust became a major focus in the days that followed, and ever since then, he has been the steady hand at the wheel – caretaker, coder, and builder rolled into one.

“It’s… a lot,” admitted Simone. “I do struggle with it. I definitely had, even recently, some burn-out moments, and I need to be careful to balance the perceived need to keep up with the game and the players’ necessities and nurturing my own will to keep going.”

At the same time, he recognized that he now has a lot more freedom in terms of how he can approach the game.

“In a sense, I think my most important job is not losing sight of the whole, and identifying what needs to be prioritized to keep things going.”

Lumen et Umbra: breaking free of the Diku mold

So what is LeU, and how has it held Simone’s attention for all these years?

At its core, the game is a multiplayer, text-based hack-and-slash. Which… yeah, doesn’t sound all that unique, until you dive into some of the influences and inspiration that have led to the most recent version: 3.0.

Simone himself describes LeU as “adjacent to what is currently understood as the ARPG genre (Diablo, Path of Exile, Torchlight, etc.), while retaining a bit more of the adventure and dungeon crawler elements typical of the precursors of the genre: you may find yourself spending some time solving a puzzle or finding a key, between one slaughter and another.”

Like many games of its era, Lumen et Umbra began as a modified DikuMUD – a popular MUD codebase of the time.

But over the last few years, Simone rebuilt most of LeU’s core systems from scratch. Not just for modernization, but to free the game from foundational mechanics that he felt were limiting it.

Re-imagining combat in LeU

One of Simone’s biggest accomplishments was reworking “wait time” – a type of cooldown system that prevented characters from acting for a time after using an ability.

The problem wasn’t that there were cooldowns, per se. Rather, it was that players could force their enemies to go into wait time, too. And in wait time, players and mobs alike would be stuck in cooldown mode, doing nothing but passive attacks while combat scrolled by…

Simone found that design to be extremely overbearing.

“It hinders the design space of encounters from the builder’s point of view,” he explained. “You can give a lot of spells and abilities to mobiles… but players will first and foremost try to prevent them from using them. It’s a great, and boring, equalizer.”

But the concept was so deeply embedded into the mechanics that it couldn’t simply be removed. Not without re-imagining everything built upon it: spells, abilities, combat flow, you name it.

It was a ton of work (literally, about 6 years worth!), but for Simone, it was worth it.

To celebrate the culmination of all that hard work, he even put together a silly trailer:

“It felt like removing an oversized old stinky sofa from a room and suddenly having so much more space for fun things to decorate it with,” he said.

By reworking how wait time functions, he opened space for more dynamic combat.

Instead of funneling every strategy into locking enemies down, abilities could become more expressive, encounters more varied, and pacing more fluid.

Classes with personality

One result of Simone’s combat overhaul was giving each class its own core mechanic – a feature that shapes how abilities work and encourages distinct playstyles.

For example:

- Monks build Combinations by never using the same ability twice in a row.

- Warriors fight through a Sequence of Opening, Follow Up, and Closure, with skills behaving differently at each step.

- Mages harness Resonance, swapping elements to regain energy or focusing until they transform into a pure elemental form with access to new, powerful spells.

Spells and skills in LeU are designed to be more than just a line of text that says how much damage you did.

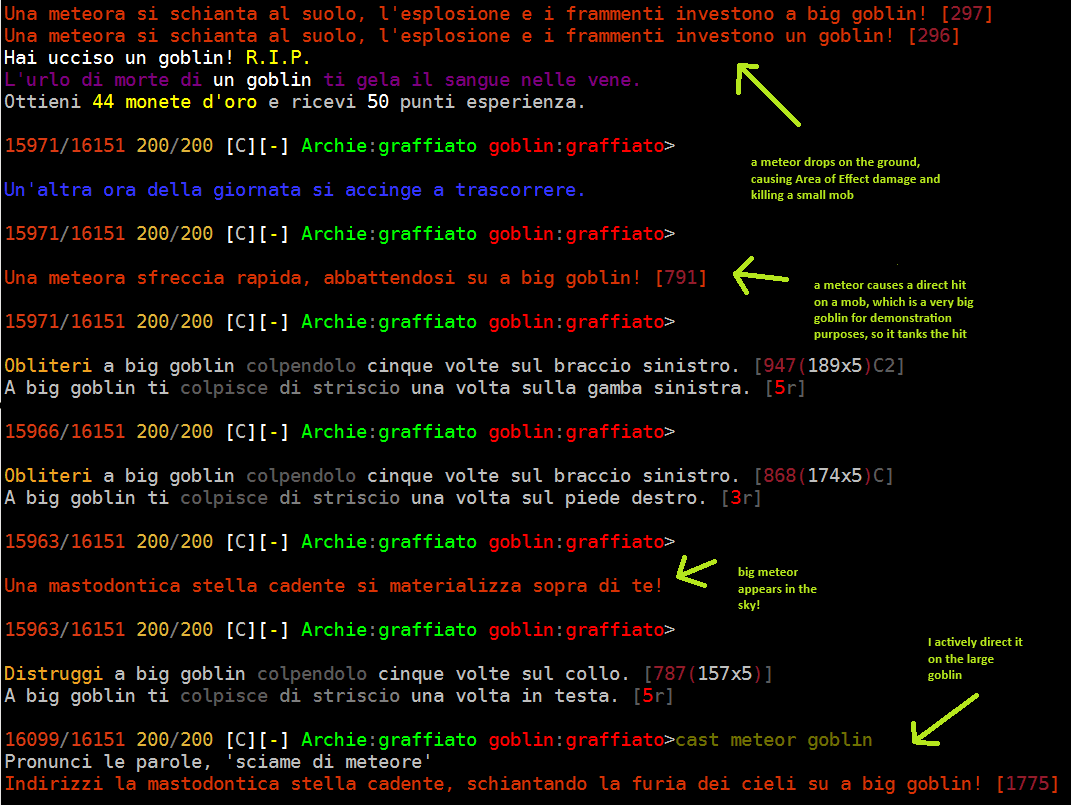

Meteor Swarm, for instance, now unfolds as a meteor shower with random strikes over the course of about 60 seconds – and sometimes a giant meteor appears, giving you the chance to direct it onto an unlucky target:

Full, plain text versions of the above example:

16151/16151 200/200 [-][-] :* :*>cast meteor swarm goblin

Pronunci le parole, ‘sciame di meteore’

Apri uno squarcio nella realta, evocando uno sciame di meteore!

Una meteora sfreccia rapida, abbattendosi su a big goblin! [948 !L]

Una meteora si schianta al suolo, l’esplosione e i frammenti investono a big goblin! [450C]

Una meteora si schianta al suolo, l’esplosione e i frammenti investono un goblin! [1187(297×4)]

Hai ucciso un goblin! R.I.P. [(x4)]

L’urlo di morte di un goblin ti gela il sangue nelle vene. [(x4)]

Ottieni 142 monete d’oro e ricevi 200 punti esperienza.

15971/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:graffiato goblin:graffiato>

Una meteora si schianta al suolo, l’esplosione e i frammenti investono a big goblin! [297]

Una meteora si schianta al suolo, l’esplosione e i frammenti investono un goblin! [296]

Hai ucciso un goblin! R.I.P.

L’urlo di morte di un goblin ti gela il sangue nelle vene.

Ottieni 44 monete d’oro e ricevi 50 punti esperienza.

15971/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:graffiato goblin:graffiato>

Un’altra ora della giornata si accinge a trascorrere.

15971/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:graffiato goblin:graffiato>

Una meteora sfreccia rapida, abbattendosi su a big goblin! [791]

15971/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:graffiato goblin:graffiato>

Obliteri a big goblin colpendolo cinque volte sul braccio sinistro. [947(189×5)C2]

A big goblin ti colpisce di striscio una volta sulla gamba sinistra. [5r]

15966/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:graffiato goblin:graffiato>

Obliteri a big goblin colpendolo cinque volte sul braccio sinistro. [868(174×5)C]

A big goblin ti colpisce di striscio una volta sul piede destro. [3r]

15963/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:graffiato goblin:graffiato>

Una mastodontica stella cadente si materializza sopra di te!

15963/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:graffiato goblin:graffiato>

Distruggi a big goblin colpendolo cinque volte sul collo. [787(157×5)]

A big goblin ti colpisce di striscio una volta in testa. [5r]

16099/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:graffiato goblin:graffiato>cast meteor goblin

Pronunci le parole, ‘sciame di meteore’

Indirizzi la mastodontica stella cadente, schiantando la furia dei cieli su a big goblin! [1775]

16099/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:graffiato goblin:graffiato>

Una meteora si schianta al suolo, l’esplosione e i frammenti investono a big goblin! [298]

15971/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:scratched goblin:scratched>

A meteor crashes to the ground, the explosion and fragments hitting a big goblin! [297]

A meteor crashes to the ground, the explosion and fragments hitting a goblin! [296]

You killed a goblin! R.I.P.

A goblin’s death scream chills your blood.

Earn 44 gold and receive 50 experience points.

15971/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:scratched goblin:scratched>

Another hour of the day is about to pass.

15971/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:scratched goblin:scratched>

A meteor hurtles past, crashing into a big goblin! [791]

15971/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:scratched goblin:scratched>

You obliterate a big goblin by hitting it five times on the left arm. [947(189×5)C2]

A big goblin glancingly hits you once on the left leg. [5r]

15966/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:scratched goblin:scratched>

You obliterate a big goblin by hitting it five times on the left arm. [868(174×5)C]

A big goblin glancingly hits you once on the right foot. [3r]

15963/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:scratched goblin:scratched>

A gigantic shooting star materializes above you!

15963/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:scratched goblin:scratched>

Destroy a big goblin by hitting him five times in the neck. [787(157×5)]

A big goblin grazes you once in the head. [5r]

16099/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:scratched goblin:scratched>cast meteor goblin

You say the words, ‘meteor swarm’

You direct the gigantic shooting star, unleashing the fury of the heavens upon a big goblin! [1775]

16099/16151 200/200 [C][-] Archie:scratched goblin:scratched>

A meteor crashes to the ground, the explosion and fragments hitting a big goblin! [298]

“It’s not just about numbers anymore,” Simone said. “Abilities interact with your toolkit, and sometimes with other classes’ toolkits, too.”

But none of this would have been possible if the game hadn’t gotten away from that core lockdown mechanic.

Simone admitted he could fill twenty pages explaining the details of Lumen et Umbra’s systems, but the philosophy behind them is simple:

Don’t just expand on MUD conventions – question them.

And if they don’t make sense for the game: be willing to break them to build something better.

Challenges in game progression

Simone wasn’t sure if Lumen et Umbra’s challenges could be called unique, but he admitted that breaking away from genre conventions does come with complications.

“With the way classes are set up, remort isn’t really an option,” he said. Multiclassing exists, but it follows strict rules that fit the game’s overall design. Player wipes were never part of LeU, and Simone knew they wouldn’t sit well with his playerbase, either.

The question, then, is how to keep the game interesting for longtime players without making newcomers feel like they need infinite time to catch up.

Simone approached the challenge in a couple of ways.

First, he spent many an hour finding a balance between horizontal progression (building variety and choice) and vertical progression (simply getting bigger numbers).

For example:

- Vertical progression: upgrading from a +1 helmet to a +2 helmet.

- Horizontal progression: choosing between 5 different helmets, each with trade-offs that tilt your character in different directions.

“Horizontal progression is far harder to achieve, but it’s also where games often fall short,” Simone explained.

By focusing on it, he created more ways for players to experiment and differentiate themselves – without relying only on level or gear grinds.

Another way Simone addressed the challenge was by shifting rewards away from pure numbers.

In LeU, success now depends on timing abilities, managing resources during long fights, and keeping cooldowns ready for the right moment. He estimated that new players can become competitive – within about 5% of top performance – after just a couple months of regular play.

“It’s never going to be perfect, but I’m not going to stop trying,” he said.

Building for accessibility

Speaking of challenges, accessibility is one of the toughest ones Simone has faced.

“There are two main reasons why this is a significant problem for me,” he said. “One is that I always wanted a robust overland system, which is inherently hostile to screen reader users. The other is that I really like using color to communicate, and that doesn’t translate to screen readers at all.”

For the overland map, he has experimented with tools like autowalking on roads, fast travel between landmarks, and procedural descriptions that use landmarks as reference points.

Still, he felt there was more work to do – ideally, some way to give players an idea of their immediate surroundings and a “general direction” navigation system.

On the color front, Simone has already taken steps to ensure that information isn’t conveyed by visuals alone. Almost everything is represented with proper text or readable symbols.

He’s also laying the groundwork for a dedicated screen reader mode: a pared-down output designed specifically for screen readers, with options to filter out unnecessary information.

His earlier rework of combat messaging already helps here. By reducing text spam and customizing what each player sees, he created a foundation for accessibility improvements.

“There’s still a lot of work to be done to reach a point where combat feels comfortable on a screen reader,” he said, “but at least it’s a solid starting point.”

Lessons learned while rebuilding LeU

When asked about lessons learned, Simone emphasized the importance of listening to players – but also the need to interpret what they really mean.

“Listen to the players and don’t dismiss their feelings or claims,” he advised. “And be very mindful of this: don’t do what they ask.”

That might sound contradictory at first, but it’s not.

Once in a great while, a player suggestion will be so thoughtful and well-reasoned that it’s ready to implement right away, he explained. “When that happens, immediately do it and celebrate it. Because that’s one in several thousand pieces of feedback.”

Most of the time, though, requests need to be unpacked.

“What you usually need to do is absolutely not do what they ask and be very tactful about it. Then, from there, process the feedback and figure out what they actually want and/or need. There is a big disconnection between the player and dev points of view which is extremely hard (and maybe impossible) to properly, fully, reconcile.”

Even so, Simone stressed that feedback almost always comes from a place of passion:

“Players will almost never post feedback to make the game worse. Processing the feedback you receive, filtering out the direct requests and finding the reasons why the requests are made is the first step toward a better game, and a better relationship with your playerbase.”

Always have a reason

Simone also stressed the importance of working with intention.

Developers should avoid refactoring just to make code prettier, over-optimizing systems that aren’t bottlenecks, or adding and removing features without clear purpose – especially when those changes can affect active players.

“It’s better to spend time thinking and clearing your mind than doing things without focus,” he said. “It’s also the best possible moment to play/read/watch/talk and find more inspiration somewhere.”

In fact, breaks are an important part of development – not just for helping the ideas flow, but for maintaining one’s well-being. And it’s hard to take them when you’re the only admin there.

“Take care of yourself, and don’t do this alone,” he advised. “You want to make a game alone? Go make a platformer. A shooter. Even a roguelike. Don’t do a persistent multiplayer world. Take me on my word on this. Please.”

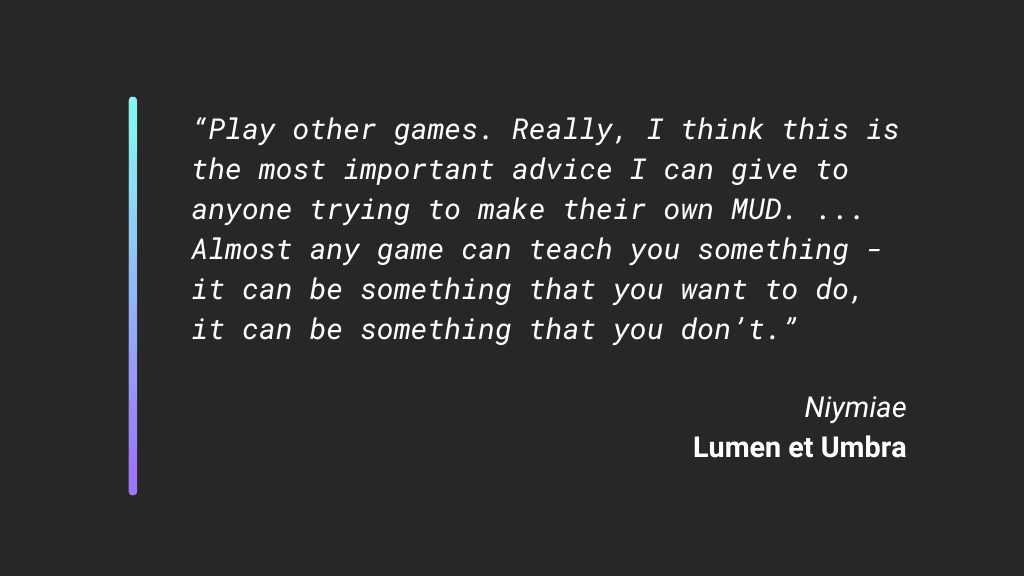

Advice for aspiring developers

When asked what resources he’d recommend, Simone didn’t point to books or codebases. His answer was simple: play more games.

“I think this is the most important advice I can give to anyone trying to make their own MUD,” he said. “Almost any game can teach you something – it can be something you want to do, it can be something you don’t.”

For Lumen et Umbra, Simone drew inspiration from a wide range of games:

- Itemization systems from Path of Exile, Grim Dawn, and World of Warcraft.

- Dialogue mechanics from cRPGs like Pillars of Eternity and Disco Elysium, adapted for a multiplayer environment.

- Death recovery from Souls games, where you reclaim lost XP at the place you died.

- Even a wordle-style puzzle for unlocking magically sealed chests.

Itemization, for example, refers to the systems that define how items are built, how they influence your character, and how you interact with them. By reworking this system, Simone blended familiar concepts for Circle/Diku players with new mechanics inspired by ARPGs.

Exiting the echo chamber

What frustrates Simone most about MUD development is how insular it can be. “One thing that stresses me out a lot when talking about MUDs is how little the genre seems to look elsewhere, while being constantly self-referential,” he said.

There’s nothing wrong, of course, with games staying within the classic guidelines if that’s what they’re trying to do. Rather, the frustration for Simone is more about the lack of alternatives, especially among hack-and-slash MUDs.

His closing advice was direct:

“Please, play more games and let yourself be inspired by their creativity, their differences, and even their issues and their failures.”

Looking ahead: what’s next for LeU?

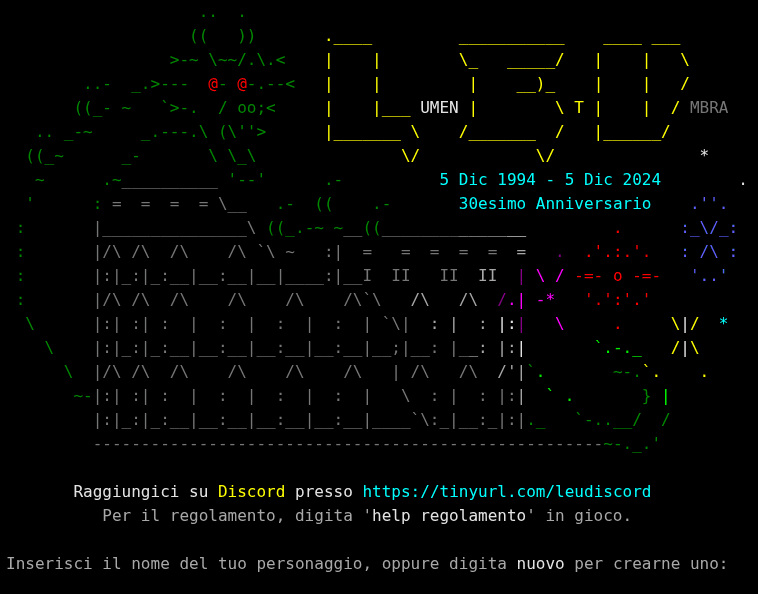

After nearly 6 years of work, Simone released the latest major version of Lumen et Umbra in April 2025 – a huge milestone.

Now, his focus is twofold: keeping up with player feedback and building new content that takes advantage of the systems he’s put in place.

The centerpiece of upcoming content is a dynamically built dungeon. Collecting keys will unlock new wings to explore, each one harder than the last. Your choices along the way will shape what you encounter – from biomes to handcrafted rooms, enemy behavior, and loot.

In pure ARPG fashion, Simone is also designing about 30 new unique items with special powers. The dungeon will scale to match the size of the group but also include a fixed-difficulty mode balanced specifically for groups of 3 players.

That mode won’t just raise the numbers – it’ll feature different bosses, new abilities, and unique mechanics. It’s an interesting idea, and not something I often see in MUDs, so I can’t wait to hear how it works out.

Returning to the overland map

The other project Simone is eager to revisit is his overland system, complete with an ASCII light engine and real-time GMCP updates.

“For once, this desire isn’t directly tied to gameplay,” he said.

“I want people to be able to wander around in a larger world, discover hidden paths, secret places, watch the sun set and bathe the woods in shades of pink, walk alone in the night and hide in a cavern, waiting as the patrol passes by the entrance until they are far enough to exit safely, as the light from their torches faded away.”

You can see a few examples here:

“It’s a lot about mood, atmosphere and sense of place,” said Simone.

By introducing dynamic visuals, he hopes that players will experience the world in a way they might not otherwise through descriptions alone.

Acknowledgements

Simone was quick to acknowledge the community that has kept Lumen et Umbra going.

“As much as I like to complain about their complaints from time to time, I’d like to sincerely thank all the players that are sticking with the game through its highs and lows,” he said. “They’ve been extremely patient waiting for the new version, and they’re the ones who have to deal with my decisions, my mistakes, and everything else that comes with it.”

He gave special thanks to:

- Kyrus, for his tireless work on the Mudlet package.

- Xenon, for spreadsheet support and maintaining the helpfiles.

Simone also credited the wider MUD Discord as an important sounding board. It gave him space to clarify ideas and – most importantly – to receive feedback from people outside his own playerbase.

“The amount of fresh perspectives, different takes, pushbacks and comments were absolutely central in keeping me on track,” he said.

A great big thank you to Simone for taking the time to walk me through his experiences and his work on Lumen et Umbra! It was fun to learn about, and shine a light on, an Italian MUD.

Thinking back on Simone’s story, the name “Lumen et Umbra” seems like a fitting description for all the ups and downs, the highs and lows he’s experienced. May the years to come be filled with more light than dark. 🙂

By the way, in case you’re curious: “Simone” is a male name in Italy, but “Niymiae” came from his main character in World of Warcraft, a female Rogue he played for years. Even before WoW, Niymiae appeared in short stories Simone wrote. Some of the characters from those tales still live on today as NPCs across different games and worlds!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Lumen et Umbra about?

Lumen et Umbra is a hack-and-slash game played using text instead of graphics. It was heavily inspired by ARPGs like Diablo, Path of Exile, and Torchlight. Each class (Warrior, Monk, etc.) is distinct and has its own unique playstyle.

Can I play Lumen et Umbra in English?

Unfortunately, no. While it does have some English language support, much of the game is only available in Italian.

What does “Lumen et Umbra” mean in English?

“Lumen et umbra” is Latin for “light and shadow” or “light and darkness.”

When was the game created?

Lumen et Umbra has been around since 1994 and celebrates its anniversary on December 5th.

Leave a Comment