Cryosphere is a long-running science fiction MUD set in an alternate timeline where a British Space Empire reigns supreme. Built on a custom C++ codebase, it quietly introduced support for Unicode and Lua ahead of its time.

Dev tools aside, one of Cryosphere’s most interesting features is how it tells stories.

Influenced by LucasArts adventures and early plot-driven CRPGs, the game runs on an elaborate conversation system that favors dialogue and discovery over grind.

In today’s interview, Morwen, the game’s lead developer and co-writer, shares how Cryosphere got started, the big decisions that shaped its design, and what’s next on the roadmap.

Table of Contents

Meet Morwen: award-winning developer, musician, and writer

Morwen, known IRL as Abigail Brady and in-game as Fleet Admiral Orange, is a London-based developer who works in the film industry.

In 2018, she received an Academy Scientific and Engineering Award for her work on the compositing software Nuke. When she’s not writing code, she enjoys playing music and organizing gigs.

In the late ’90s, Morwen helped launch Cryosphere while studying computer science at the University of Southampton. Nearly three decades later, she’s still maintaining the engine, refining the story, and guiding the game into its next chapter.

Both Niymiae and Asmodeus recommended Morwen for an interview, and it’s not hard to see why! When I pinged her on Discord back in August, she happened to be in the middle of writing an email to me about Crysosphere. 😂 It seems this post was just meant to be!

Learn more about Morwen and her work at morwen.net.

Cryosphere: the origin story

Work on Cryosphere began in 1997 when a small group of computer science students decided to create their own science fiction multi-user dungeon (MUD).

The plan was ambitious: build a custom codebase from scratch in C++, with networking, softcoding, and world-building all handled in-house.

Morwen, in her first year at university, was invited early on to help with networking (the socket kind).

“I got into MUDs by accident,” she said. “I was recruited to work on Cryosphere before I had actually used one.”

Around the same time, she started exploring an AberMUD called TerraFirmA and quickly found herself hooked. Before long, she was shaping Cryosphere’s codebase, MusicMUD, and helping out with world design.

What started as an experiment at college became a long-term collaboration. In time, Morwen took over as head coder, refining the engine while working alongside a community of builders and players eager to test new ideas.

“I’d written games before, for my own amusement – even an adventure game or two – but here we had a community of builders and players eager to go already,” she recalled.

As time went on, Morwen’s role varied depending on the game’s needs and its active team members.

“We’ve just done a server migration, and I took a leading part in that,” she said. “Since then, I’ve been trying to be around when I can, to be a friendly name.”

Premise and core gameplay

So what’s Cryosphere all about, exactly? Well, Morwen describes it as “a multiplayer text-based satirical science fiction game” – a mouthful that still doesn’t quite capture the scope of what the game attempts.

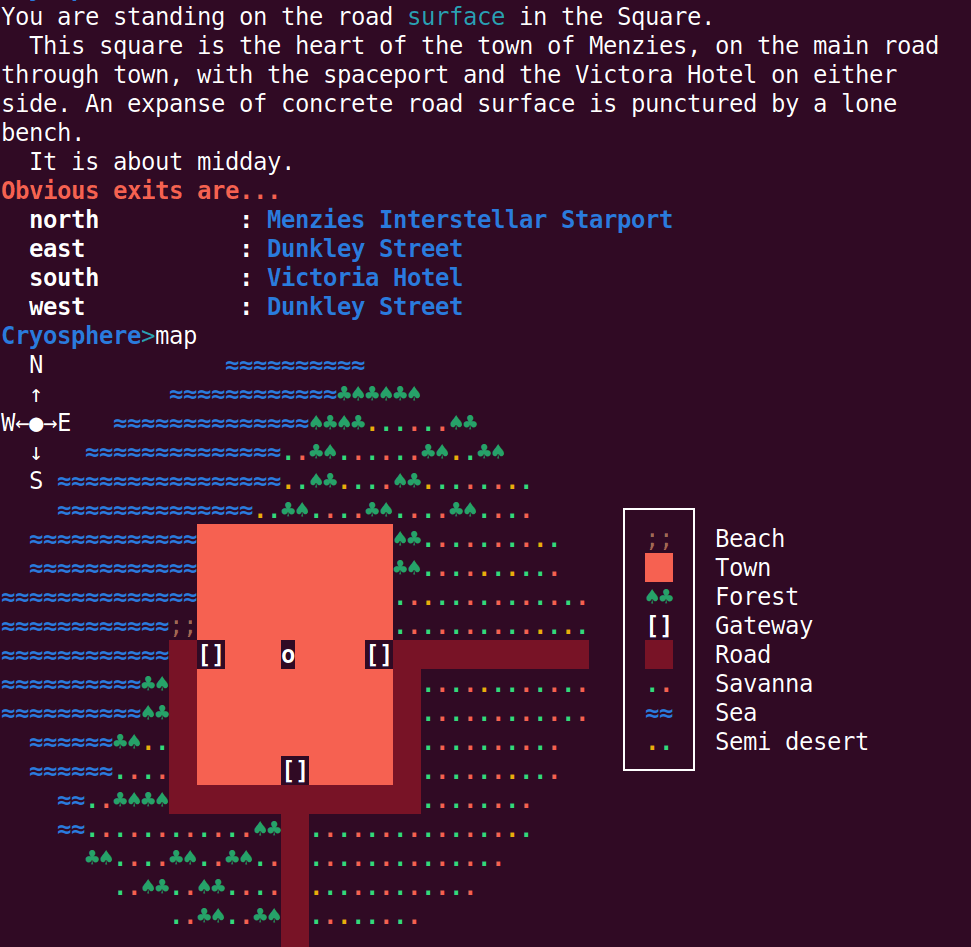

It takes place in the year 2063, in an alternate timeline where the 21st century became the age of space exploration. History diverged in 2001, giving rise to a geopolitics of competing nation-states beyond Earth – most notably the British Space Empire, the player’s home faction.

Starting as Cadets, players explore, take on missions, and interact with the setting’s many outposts and personalities. Gradually, the tone of the story shifts as players begin to realize that perhaps the Empire’s version of events isn’t the only one.

Ultimately, it’s a layered world that invites players to question the systems they serve and the stories they’re told.

In fact, storytelling is a much bigger part of Cryosphere than Morwen and her friends had originally anticipated.

From adventuring to storytelling: conversation as a core focus

In its early days, Cryosphere actually looked more like the AberMUDs that inspired it – zones filled with puzzles, exploration, and a sprinkling of combat.

That changed when the team introduced a complex conversation system that rewired how players interacted with the world.

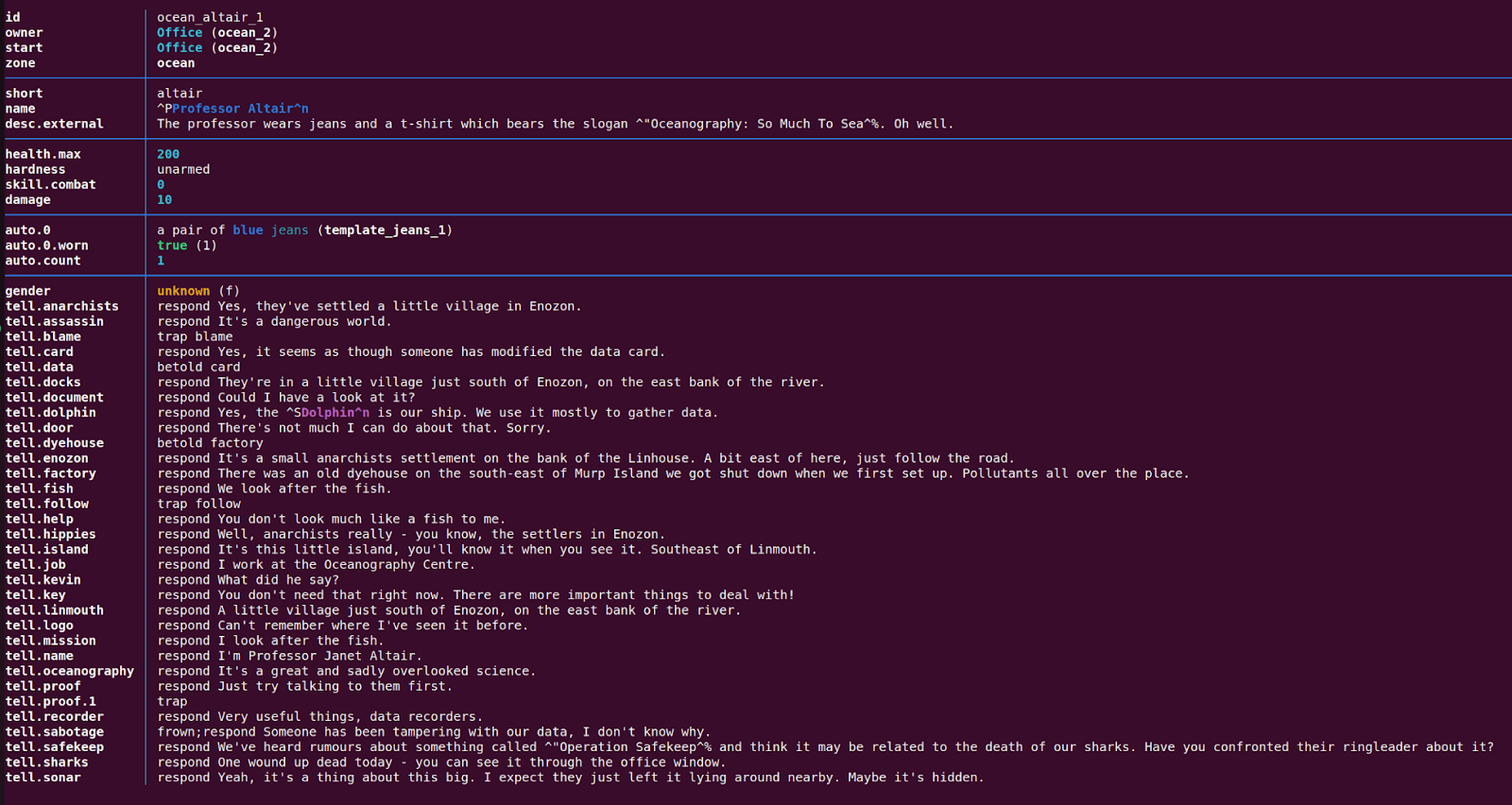

Every NPC in Cryosphere, including some hostile mobs, has a branching tree of responses influenced by classic CRPGs. Players can ask questions, follow threads, and uncover storylines.

“The conversation tree system completely altered the way we were building the world and our missions,” Morwen said. It shifted the tone of the game from a series of challenges to a series of stories – from rooms and puzzles to motives and plots.

In short, the conversation system became a foundational part of Cryosphere’s identity as a MUD.

The only drawback, Morwen admits, is that the keyword-based interface shows its age. She’s been exploring ways to modernize it, possibly by layering a choice-based interface on top of the existing system.

“Not easy when there are several thousand pieces of dialogue already written,” she said.

Accessibility efforts: then and now

When I asked Morwen about accessibility, she mentioned that it’s been part of Cryosphere’s design discussions since the early 2000s.

At the time, most requests from screen reader users focused on toggles – the ability to disable ANSI color codes or shorten room descriptions so navigation would be faster and cleaner.

More recently, she’s been working on a full accessibility overhaul aimed at removing all ASCII art and replacing it with screen reader-friendly alternatives for maps and tables. The update will also introduce structured data that can describe layouts and exits in a consistent, readable way.

These latest improvements were delayed during a slow period of development, but they’re now close to release. “We should have done this much sooner,” she said.

Lessons in organic development

What else has Morwen learned over the years? For one thing, decades of coding and maintaining Cryosphere have given her a long view of software design:

“I’ve known systems at work, and in hobbies, where someone (sometimes me) has tried to think ahead of time and design an interface and a library that is complicated enough it can solve all anticipated problems,” she said.

“I have also known systems that have a complex interface that still doesn’t do what I want and then they’re a bugger to change.”

The kicker? These are often the same systems.

“These days I prefer to design internal interfaces much more organically – thinking about future requirements but not immediately trying to address them, but making them easier to change as new requirements come along,” she explained.

Makes sense. And not only that, it complements advice from other interviewees, like Volte6, who recommends getting to the playtesting stage sooner rather than later.

Simpler systems are easier to ship, which gets you to playtesting and feedback faster. To Morwen’s point, this can save coders from spending months on a system that ultimately frustrates players and is a pain to change after-the-fact.

Innovation and technology in Cryosphere

Lastly, it wouldn’t be fair to talk about Cryosphere’s past challenges without also giving a nod toward its innovations in softcode and text rendering.

In the early days, the founders wanted a flexible way to build game content without reinventing the wheel or getting tied down by a complex system. Morwen tested several existing programming tools in search of one that was simple, powerful, and embeddable.

“S-Lang and Guile were two that we tried in the ’90s but those didn’t quite fit,” she recalled. “A little bit later I have memories of looking at a JavaScript library and being horrified at the complexity of its API.”

Luckily, a member of the team (plett) came across Lua, a small, fast language that could safely run inside their C++ engine.

Lua has since been embedded into many games, but back in 2002, Cryosphere was already using it to handle its missions and in-game interactions – something few other MUDs were doing at the time.

A renewed focus on text

Morwen’s background also gave the game a head start in another area: text itself.

Her first job after university involved working on Unicode support for Linux, and she carried that knowledge straight into the game. By 2003, Cryosphere could display any language or symbol properly – an uncommon feature among MUDs at the time.

More recently, she’s been experimenting with better font rendering in the custom-built web client, Chrysalis, letting players enjoy proportional text while keeping ASCII art neatly aligned.

“There’s so much text on the web, and yet MUDs seem to remain just out of reach for so many people. I’d like to reduce that barrier between the web and the MUD.”

The importance of tooling and testing

For all its technical ambition, Cryosphere’s biggest challenge has often been its tooling – the behind-the-scenes scripts and utilities that keep the game running.

Morwen still maintains a “slightly horrific” (as she calls it) collection of Perl scripts written years ago to automate routine tasks, though she’s been rewriting them in Python as needed.

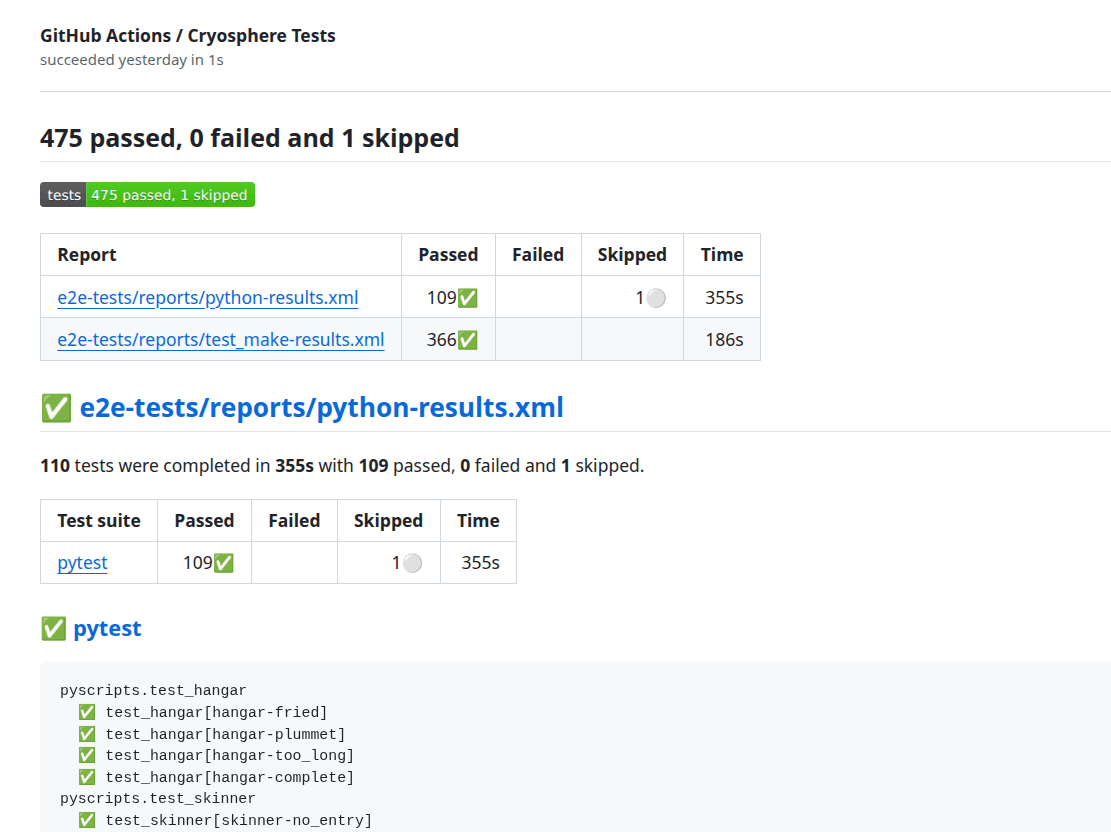

Around 2010, she began writing automated end-to-end (e2e) tests based on her experience working on Expect. They were designed to simulate gameplay by running commands, checking outputs, and verifying that things behave as expected.

Over time, these tests gradually expanded to cover most of the game’s systems.

Last month, Morwen added a continuous integration (CI) process, so that every code change now compiles and runs the entire test suite automatically.

Her takeaway is clear: every game should have automated testing.

“In any volunteer project I’ve worked on, recruiting testers is hard,” she said. “[Automated tests] let me be more confident about changes I make, and allow our testers to use their time better.”

What’s next for Cryosphere

Cryosphere’s next major update, version 3.0, is already in progress. The new branch focuses on accessibility improvements, modernization, and a general cleanup of legacy code (made possible by the newer features of C++).

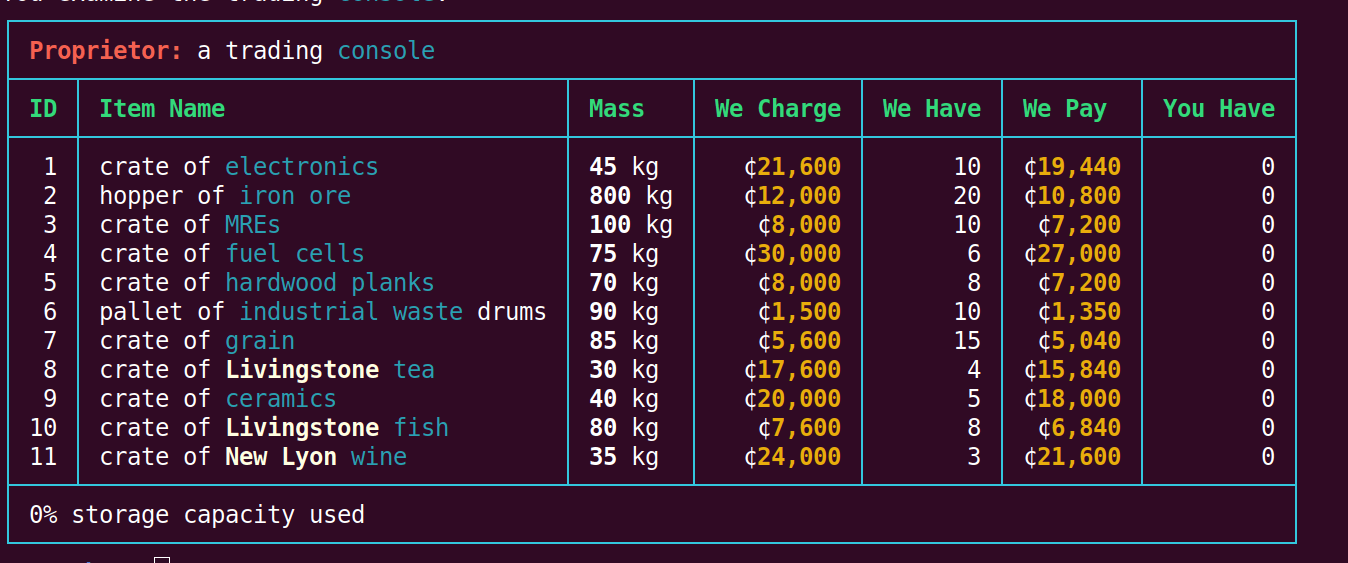

But Morwen’s plans go beyond refactoring. She’s also introducing new ways for players to engage with the world. One long-running idea, player-owned and operated ships, is finally becoming reality.

“It’s been a kind of in-joke for years,” she said, “but this time it’s serious.”

The new gameplay loop will let players take on trading and transport activities, turning the economy itself into a form of interactive storytelling.

Alongside that, the team is experimenting with procedurally generated starports, including one that serves as a gateway to a new, combat-focused zone called New Australia. The first new zone in over a decade, it’ll provide players with a fresh experience.

Credit where due

Morwen was quick to credit the people who helped shape Cryosphere – from the original founders, MusicMaker and Cryogenius, to longtime contributors Gareth, Serriadh, plett, Daz, and Ellyll, as well as many others over the years. She also thanked Bingo and Vesper for their more recent help with testing.

“It’s literally a joint effort,” she said. “The MUD would never have got started without them, and it wouldn’t have got as far as it did without everyone who’s joined along the way.”

A big, warm thank you to Morwen for introducing me to Cryosphere and giving me a peek behind the curtain to better understand how the game was made and where it’s headed next! I learned a lot, and I had fun exploring the Cryosphere. The hubwards/rimwards directions were a new experience for me and made the MUD feel fresh and different.

If you’d like to explore the Cryosphere yourself, you can point your client to cryosphere.org port 6666 or join from your web browser. And don’t forget to check out the handy Starting guide!

Frequently Asked Questions

What kind of game is Cryosphere?

It’s a multiplayer game played with text instead of graphics, favoring intrigue and dialogue over combat. Players start as Cadets in the British Space Empire and work their way up the ranks. As they do, they discover that things aren’t always what they seem.

Is Cryosphere still playable?

Absolutely, and the game would love to have you! Visit cryosphere.org for the latest instructions and quick start guide.

How old is Cryosphere?

The game has been around since 1997 and celebrates its anniversary on October 19.

Leave a Comment