It’s the ‘90s. You’re playing a multi-user dungeon, slaying goblins, arguing about the latest updates with a wizard, and generally living your best text-based life.

But there’s a problem – your world is isolated.

Sure, the game might have an active player base, but it’s an island, disconnected from all the other MUDs out there. You have no idea what’s happening in the other virtual worlds, nor can you easily chat with your friends who prefer to hang out on some other game.

Enter the InterMUD communication network, a cross-MUD chat system.

If each MUD was its own medieval castle, then the earliest InterMUD was a network of ravens flying messages back and forth. You could talk to your friends hanging out on another server, complain about balance changes across multiple games, and share dev tips without having to tab out to a forum.

In today’s post, we’ll dive into the history (albeit abbreviated!) of how this all started, how it evolved, and why it still matters today.

…or does it? Read on to find out.

Table of Contents

- The early days: why did we need an InterMUD communication network?

- The first experiments and the need for better tools

- Tim Hollebeek and the birth of InterMUD 3

- The rise and fall (and rise) of InterMUD 3

- IMC2 and other protocols used by MUD games

- Connecting lonely worlds: IberiaMUD and the spirit of InterMUD

- Do we still need (an) InterMUD?

- Where one flame goes out, another will spark

The early days: why did we need an InterMUD communication network?

Back in the earliest days of MUDs, every game was a walled garden. Each one had its own player base, drama, and unique theme, mechanics, or flavor tucked behind those walls.

Exciting new developments were happening all the time, but there was no way to talk to people on another game without physically logging into their server.

For game admins, this was frustrating. Developers had no easy way to collaborate or share ideas across different games in real time.

And if a game shut down? Poof – community gone, unless they had the foresight to meet up elsewhere.

So, naturally, some smart people thought, “Hey, we should link these worlds together.”

The first experiments and the need for better tools

The earliest attempts at interMUD-style networking date back to the early ’90s, when The Mud Institute (TMI) experimented with connecting LPMud servers.

This early work led to InterMUD 2 (I2) – a basic, peer-to-peer system using UDP, a fast but unreliable network protocol.

Each game had to manually track the others, which meant:

- admins had to keep lists of which games existed

- any time a game shut down, everyone had to update their configs

- messages sometimes got lost because UDP doesn’t guarantee delivery

Despite the inconveniences, the system worked. It showed that real-time cross-MUD communication was possible.

Tim Hollebeek and the birth of InterMUD 3

Although the peer-to-peer system worked, developers wanted something more stable and efficient. One of the biggest contributors to that next step was Tim Hollebeek (aka “Beek”), who helped define what became InterMUD 3 (I3).

Alongside Greg Stein (“Deathblade”) and John Viega (“Rust”), Hollebeek worked on a more reliable approach that used TCP connections and a central hub known as a router.

The idea behind I3 was to simplify everything:

- each MUD connects to the central router instead of to each other

- the router handles message delivery between connected games

With I3, instead of every game being responsible for keeping track of the network, they just had to connect to the hub.

If you’ve ever heard of internet relay chat, you can think of it kind of like an IRC network just for MUDs.

InterMUD 2 vs. InterMUD 3: what’s the difference?

In a nutshell, here’s how the two systems compared:

| InterMUD 2 | InterMUD 3 | |

| Connections | Peer-to-peer (each manually tracks all others) | Centralized router (all connect to a hub) |

| Protocol | UDP (fast but unreliable) | TCP (slower but reliable) |

| Message Delivery | Not guaranteed (packets can be lost) | Guaranteed (messages are ordered and received) |

| Ease of Use | Harder (admins must manually update lists) | Easier (just connect to the router) |

| Failure Handling | If one game retires, others must manually remove it | The router automatically handles disconnected games |

You might be wondering, “What about the original InterMUD?” Well, it wasn’t called that back then – it was just an experiment. Though, you might see it retroactively mentioned as “InterMUD1” if you go digging into archives.

The rise and fall (and rise) of InterMUD 3

Like old corner shops, these networks didn’t last forever. But when one closed, another often opened to take its place – not always identical, but enough to keep people connected.

For years, a central hub of the InterMUD 3 network was a router known as gjs, hosted at intermud.org. It served as the main connection point for MUDs that wanted to join the network, relay messages, and share global channels.

But over time, gjs became increasingly unreliable. Outages became more common, and eventually, it went down for good.

Cratylus, who was working on the Dead Souls MUDlib at the time (dead-souls.net), had already been experimenting with running his own router, mostly to support developer coordination. After gjs disappeared, his router became the default fallback for many MUDs.

“For Dead Souls developers, the dead_souls intermud channel was a vital resource for development discussion and support,” he wrote on the LPMuds.net FAQ page. “I decided it was time to implement a router that the Dead Souls muds could count on.”

In a recent Discord conversation with me, Cratylus recalled how it went down:

“Beek, Rust, and Deathblade ran the original gjs router for Intermud‑3, and then it started getting flakey. So because I was developing a mudlib and wanted a stable router, I set up my own. Then gjs died, and my router became the main router. As you might imagine, there was… discourse. Controversy. Drama.”

Drama, in the MUD world?! Surely not, no…

To understand why there was drama, you need to know that the original gjs router had little in the way of moderation. It was an anything-goes environment, very unlike the Discord servers of today, where every community has guidelines in place.

Cratylus’ intermud had rules. Hate speech, spamming, and disruptive behavior weren’t welcome on shared channels, especially those meant for newbies. The goal was to provide a friendly space for developers and a stable platform for MUD communication.

“I really don’t ask for much,” he wrote in the FAQ. “Just follow the rules on the few protected channels, and adhere to their declared topics. You’re here as a guest, by choice.”

Even so, some users viewed his rules as overreach – anti-free speech even. Cratylus stood by his rules, and his router remained active and stable.

Other routers came and went. Some served as backups, others as regional options or experiments in protocol compatibility. Not all of them remained active, but a small network of linked routers continues to support the I3 protocol.

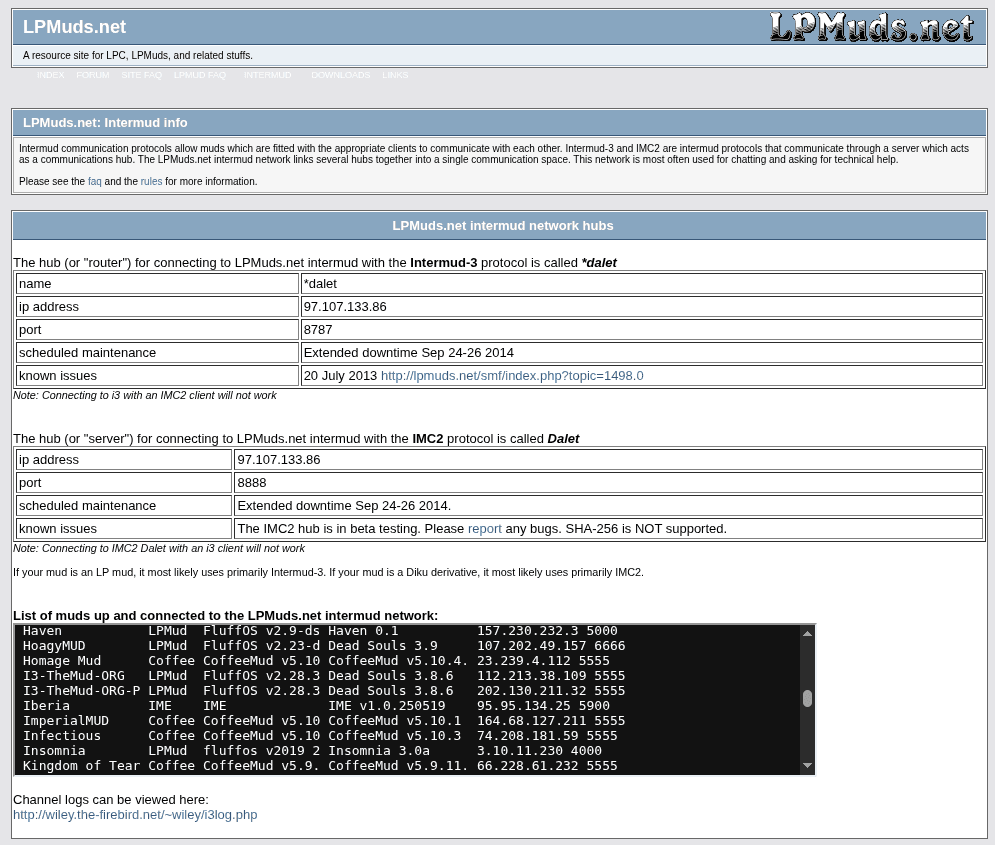

As of today, Cratylus’ router is still in service, with dozens of connected MUDs spanning various codebases. Diku-based games often use the related IMC2 protocol, which is also supported through a companion router. (More on this below.)

The network isn’t as busy as it once was, but it continues to serve its purpose: connecting otherwise isolated games and giving developers a shared channel to talk, trade ideas, or just say hello.

IMC2 and other protocols used by MUD games

While I3 became the standard for LPMud-based games, other MUD families had their own solutions to the problem.

The DikuMUD world had InterMUD Chat 2 (IMC2), which functioned a lot like I3 but was designed to work with ROM, Merc, and other Diku sytems.

Meanwhile, some MUDs, especially in Europe, kept using Zebedee Intermud, an older InterMUD 2-style network that relied on peer-to-peer UDP messages instead of a central router.

And if you were on a MUSH or MOO codebase, you might have encountered MushLink – a chat relay system that worked by logging in as a bot to pass messages between servers.

The “intermud” was really a patchwork of different systems, but they all had the same goal – connecting games and communities.

IMC2 and the bridge to I3

However, IMC2 wasn’t without its own drama.

For years, the most active IMC2 network was hosted at Mudbytes.net. But in the early 2010s, it began experiencing frequent downtime. By August 2011, users were openly discussing the decline:

“It’s been down for about a month now by my guess,” wrote Bo Zimmerman. “Cratylus, would you be able to host a new server?”

Cratylus responded that he already did – an IMC2-to-I3 bridge connected to the LPMuds.net network – but noted tensions with Mudbytes leadership.

Whatever the cause of the outage, the network never fully recovered.

Some remaining IMC2-connected MUDs migrated to Cratylus’ network using the IMC2-to-I3 bridge, which still accepts IMC2 connections to this day.

It wasn’t a seamless transition, but it kept IMC2 alive in practice, even after its original hub went dark.

My guess is that most developers probably didn’t care much about the drama and just wanted something stable that worked.

Connecting lonely worlds: IberiaMUD and the spirit of InterMUD

Even as many of the old InterMUD networks have gone quiet, some developers are still finding ways to keep the idea alive.

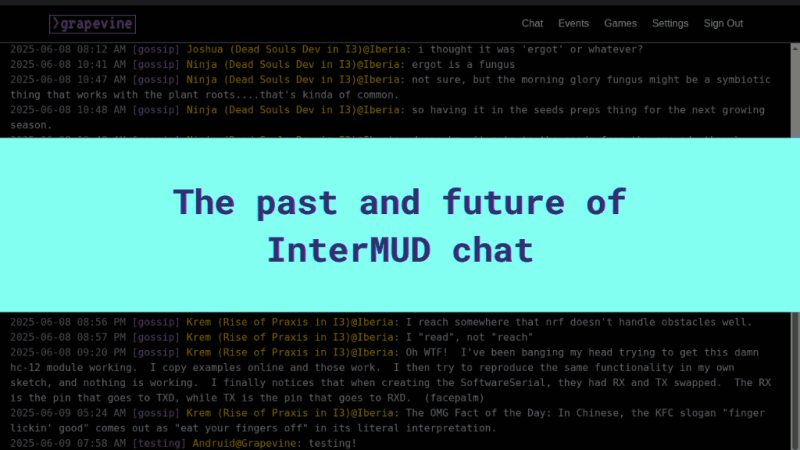

Take IberiaMUD, a multilingual game based in Portugal. In the past two years, it successfully connected to the surviving I3 network and became one of the more visible presences on Grapevine’s shared chat channels – or “gossip” network, effectively acting as a bridge between the two systems.

Unlike many games that use standard codebases like Diku or LPMud, IberiaMUD runs on a custom-built engine called the Iberia Mud Engine (IME).

Developed in Java from the ground up, IME doesn’t inherit the built-in support for intermud protocols that other MUD drivers often include. That meant Viriato had to implement the necessary features himself.

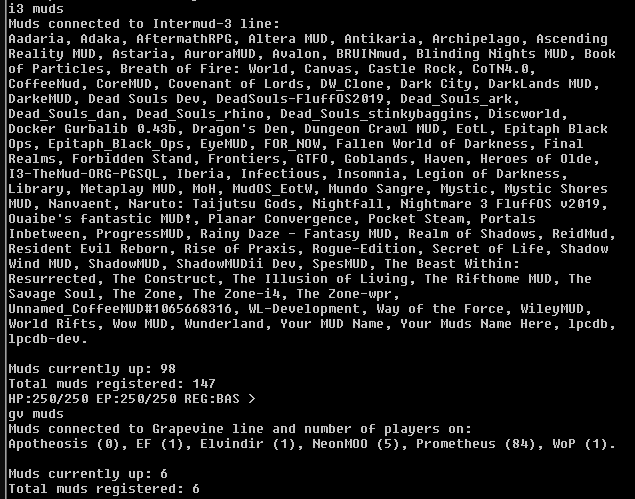

Viriato sent me a few screenshots showing his work, including the commands he’d created to list I3-connected and Grapevine-connected games:

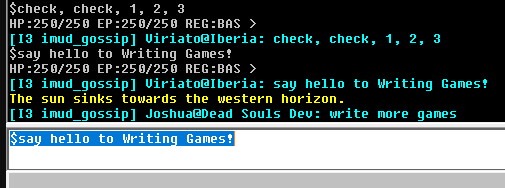

And here, Viriato calls out into the void, and the void answers:

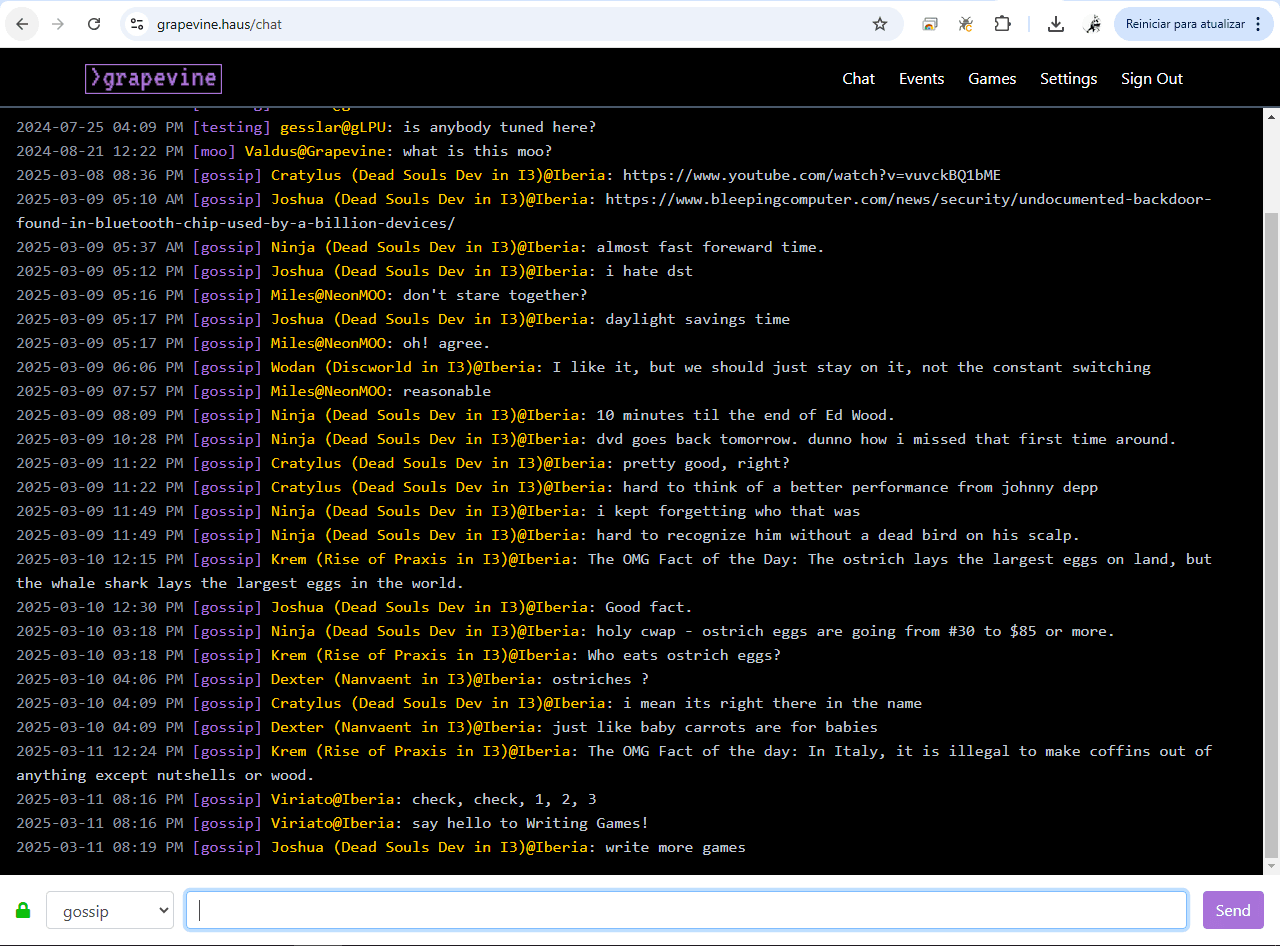

As for Grapevine… it was once a promising network for modern MUD communication (and one of my favorite listing sites, thanks to its modern look and newbie-friendly “Play” button). It provided a simpler way to link games using WebSocket and a shared protocol.

The project hasn’t seen active development in years, and its future remains uncertain. Still, it served as a bridge between communities when few others were available.

“Grapevine tried [intermud-style chat] with their Gossip.haus feature and it worked for a while, but that’s no longer maintained,” Opie told me when I asked him about his experience with the system. “I think it’s a great way to connect MUDs, without the need of leaving the MUD they are on. Like a Discord, etc., but [the Gossip network] just never really caught on.”

For Viriato, the motivation behind linking IberiaMUD to both I3 and Grapevine was part technical, part personal:

“[I did it] to not feel lonely in ‘my world’. The MUD community is small and with many sparse projects, so if we can connect and join them, it would be better overall.”

The bridge he’d created allowed him to keep talking to friends and fellow devs, even when he was the only one logged into his game.

His work also came with an unexpected silver lining:

“People from other MUDs connected to I3 began to hear about Iberia. So it is also another way to promote your MUD to other MUD players,” he said.

When I think about it, IberiaMUD didn’t just connect on a technical level – it captured the old-school spirit of what made these networks special in the first place.

And while the future of platforms like Grapevine is unclear, Iberia’s presence there shows that the desire to bridge worlds hasn’t yet gone the way of gjs.

Do we still need (an) InterMUD?

So all of this begs the question… with Discord dominating the chat scene these days, do we even need InterMUD anymore?

Game developers have been actively integrating Discord into their projects for years now, and that includes the multi-user (MU*) crowd, too. Even Viriato admitted to me that he could have just built something for Discord, if he wanted.

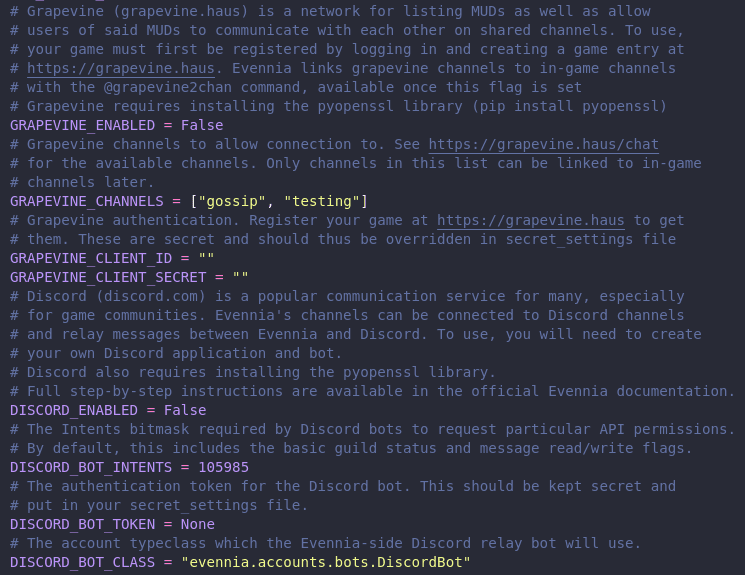

Evennia, for example, has built-in support for Grapevine chat and instructions for hooking directly into Discord. It used to support IMC2 natively, too, but not anymore.

According to Griatch:

“Evennia had native IMC2 support for a long time. It worked the same way as our other chat integrations into in-game channels. But eventually the networks shut down and we lost easy ways to debug it. So I dropped support.”

In an archived GitHub issue from 2014, Greg Taylor, the original creator of Evennia, noted that the Mudbytes IMC2 network had been offline for months. The end of another era.

Today, Discord has a lot going for it that the old systems didn’t. For one thing, it has a solid mobile app.

Being able to chat with your community from your phone while at work, get admin notifications on the go, or check in on your game’s status without logging into a terminal? That’s hard to compete with, especially among a group of aging gamers with busy RL careers.

That said, InterMUD networks still offer something unique:

- they bring cross-game chat into the game itself, meaning you can talk to players on another MUD without needing an external app – just type what you want to say into the command line and hit enter

So, is InterMUD necessary today? Probably not in the way it once was.

But does it still offer an immersive way for MUDs to connect? Absolutely.

The question isn’t whether it can survive in a Discord-dominated scene – it’s whether players still want that kind of in-game, cross-world connection in the first place.

Viriato does. But what about you?

Tip: If you want to experiment with Grapevine’s chat feature yourself, you need to register. You won’t even see the “Chat” item in the menu unless you’re logged in (which might be why so few people know about it?).

Where one flame goes out, another will spark

InterMUD has come a long way since its early days, evolving from a chaotic peer-to-peer network into a structured, centralized chat system.

In truth, this post barely scratched the surface on decades of work, collaboration, and controversy.

I haven’t played on an InterMUD-connected game since college, so I had to do a fair bit of digging to write this post. But the more I read, the more I appreciated just how much effort went into keeping these networks alive.

And who knows? Maybe the future holds even more ways to connect virtual worlds – whether it’s through modern networks, new inter-game social tools, or some other weird idea that we haven’t even thought of yet.

One thing’s for sure: MUD players will find ways to keep talking to each other, no matter what.

Many thanks to Viriato, who reached out to me to share his work and encouraged me to write this post. And to Cratylus, Griatch, and Opie for chatting with me on the subject and for sharing their thoughts.

If you have fun memories of cross-MUD chat back in the day, or if you’ve done something cool with Discord for your game, leave us a note in the comments!

Leave a Comment